Reflected Light

The industrial town of Rjukan is nestled deep in an alpine valley that creases Norway’s rugged Telemark county. For much of the year, it is also a popular tourist destination owing to award-winning scenery that includes Gaustatoppen mountain and the thundering Rjukanfossen waterfall. A short distance away, Hardangervidda National Park — the largest eroded moorland plateau in Europe — is a hiker’s paradise.

Unfortunately, Rjukan also has one rather notable downside. Sandwiched between two massive walls of stone and ice, the community spends long months in perpetual shadow. Each year, on September 28th, the sun casts its last rays upon Rjukan before disappearing behind the mountains for an extended six month winter.

The effect is palpable. In the words of local artist Martin Andersen, “Darkness is a state of mind for the people of Rjukan.”

Squeezed between light-blocking mountains, the town of Rjukan spends six months a year in darkness.

Photo credit: Mail Online

For the past 100 years, Rjukan’s leaders have struggled to find a solution for their dismal predicament. Sam Eyde, who created the town in 1905 to house workers for his local hydropower and fertilizer plants, was intrigued by the idea of building a Solspeil, or Sun Mirror, to channel light into the community. Hoping the sunshine would increase worker productivity, but finding early 20th century technology unequal to the task, he instead built a cable car to hoist workers to sunny ridges above the town.

As decades passed, Eyde’s “solution” proved less than satisfying for many Rjukans. On many days, Andersen laments, “we'd look up and see blue sky above, and the sun high on the mountain slopes, but the only way we could get to it was to go out of town. The brighter the day, the darker it was down here.”

Daniel Paida Larsen remembers walking down the street during his high school years. Looking up and seeing sunshine and blue sky, he thought: “Why can't I be there?” “I miss the sun here in winter terribly,” adds Anette Oien. “It’s just been so hard.”

In 2005, this depressing shadow got Andersen to thinking again about Eyde’s Solspeil. After all these years, perhaps the technology had finally caught up to the vision.

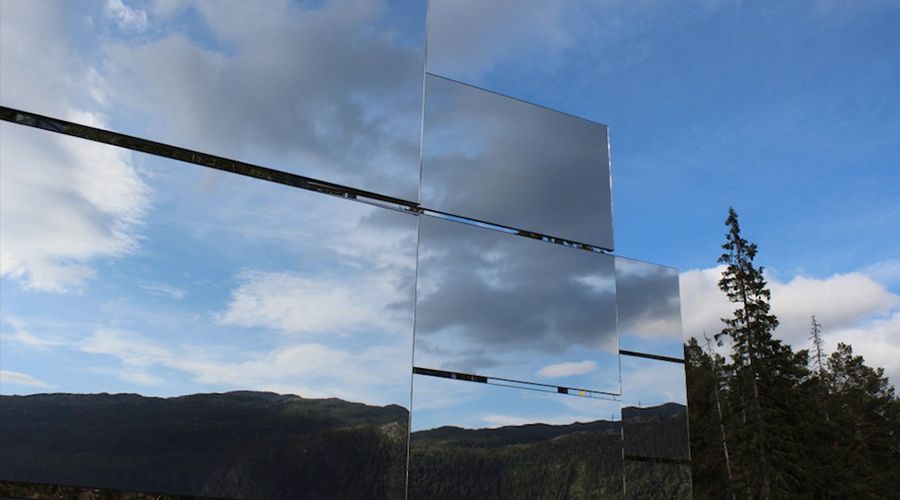

As Andersen suspected, it had. And after several years of contentious community debate, the town eventually mounted three 183–square–foot reflectors on a ridge nearly 1500 feet (457 meters) above the town. Called heliostats, the mirrors track the sun across the sky and beam a 1,476–foot–long ellipse of daylight onto Rjukan’s market square.

Newly installed reflectors cast a beam of winter light onto Rjukan’s town square.

Photo: Terje

On October 30, 2013, the gloomy Norwegian town received its first ever rays of winter sunshine.

“It's awesome,” says shop assistant Silje Johansen. “Just awesome.”

Andersen's close friend, Daniel Paida Larsen, agrees: “This goes so deep into the public sphere. It touches something absolutely fundamental in this town.”

For many of Rjukan’s 3,400 residents there is an undeniable sense of pride at having overcome Gaustatoppen’s immovable shadow. In the words of Oystein Harald Haugen, Rjukan’s World Heritage coordinator, “We want to show the world that we have managed to take the sun down to our city.”

A Modern Metaphor

The spiritual parallels between Rjukan’s remarkable story and the process of welcoming revival are striking. Indeed, only a single letter distinguishes Haugen’s comment from our own aspirations — we would bring “the Son down to our city.”

It would be easy to conclude the lead actor in this story is a clever technology, or a plucky community determined to get what it wanted. In reality, it is neither. The real star of the Rjukan saga is… well, a star. Apart from the sun’s warming light and life, there is no story.

We cry out to God with Isaiah, “Oh, that you would rend the heavens and come down…” (64:1). His life-giving presence has been missing from our communities for too long, and we need to recover it at all cost.

The phrase “come down,” which the prophet employs four times in this passage, draws a distinction between God’s omnipresence and his manifest presence. Isaiah is asking, as do we, that God would reveal himself on earth — and even more, take up residence among us.

There will always be those who question whether efforts to “bring the Son down to our city” are possible, or even necessary. In Rjukan, the resistance to Martin Andersen’s Solspeil lasted for more than five years. When asked to explain this foot-dragging, Andersen replied: “I think that living in the shade must make you afraid to dream of the sun. That’s the only way I can explain it… like the valley walls, minds without sun become somehow a little bit narrower.”

Those who believe they will never see the Son rarely keep their unbelief to themselves. Rather, they set out to convince anyone who will listen that darkness is simply the way of things. We don’t have to like it, but we do have to come to terms with it. As one Baptist minister put it in 2009: “We should not put all our hopes in revival, but should [rather] continue to preach and pray for conversions during the hard seasons… God, in His own good time…may see fit, some day, to send us the revival for which we have prayed so long!” (Compare with Haggai 1:2-3)

Of course, this is not exactly great news for the addicted, downtrodden, and oppressed. If present darkness is unlikely to lift anytime soon, where is the incentive to continue living?

Fortunately, the Scriptures do not burden us with such a bleak assessment. To the contrary, they present us with explicit instructions on how we, as God’s servants, can channel his glorious light into the darkened alleys and institutions of modern society.

God comes, in the words of Isaiah, “…to the help of those who gladly do right, who remember [his] ways…” (64:5). James adds: “Come near to God and he will come near to you…” (4:8). We are to ask him to come (Isaiah 62:6-7), prepare for him to come (Isaiah 40:3), and expect him to come (Hosea 6:3).

“The people walking in darkness have seen a great light; on those living in the land of the shadow of death a light has dawned.”

—Isaiah 9:2 & Matthew 4:16